Time Machine: The People Power of Watch Dogs

Time Machine is a series of posts revisiting pieces I wrote on various video games. The following piece originally appeared on CVG (site no longer active) on 11th Oct 2013.

I've hacked into a laptop. I'm looking out through its webcam - unattended, and giving me a clear view of the interior of a small apartment. There's pictures on the wall. A cheap couch. Out of frame, a woman's voice is humming a soft tune.

Directly across from the laptop, on the kitchen table, I can see a smartphone. A button prompt appears above it, and my thumb hovers over that button. If I wanted to, I could hack that phone with a simple press. I could obtain the owner's bank account details, then head to an ATM and help myself to her funds.

In another room, I can hear a baby crying.

It's emotional manipulation, clearly. It's laying out a fill-the-gap narrative - one of a woman, maybe a single mother, with an infant mouth to feed - and daring me to make a move. It's challenging me to weigh up concerns of privacy and morality against my own greed.

So I do. I hit the button, and instantly a popup window confirms the hack. Her details are now my details, and the GPS feature on my phone shows me directions to the nearest ATM. Just like that, I've got free money. It's too quick, too easy. Alarmingly so.

The baby continues to cry. The mother is gently cooing it, speaking in a gentle tone. She's none the wiser to what has just happened metres away, in her own home.

"This feels wrong," I say.

Kevin Shortt grins. "If you're drawing attention to yourself, stealing cars and shooting everybody, people will take notice. You walk into a store, the shop owner will pull a gun on you because he recognises you from the news. But if no one sees you do it... well, the only consequences are those from your own conscience."

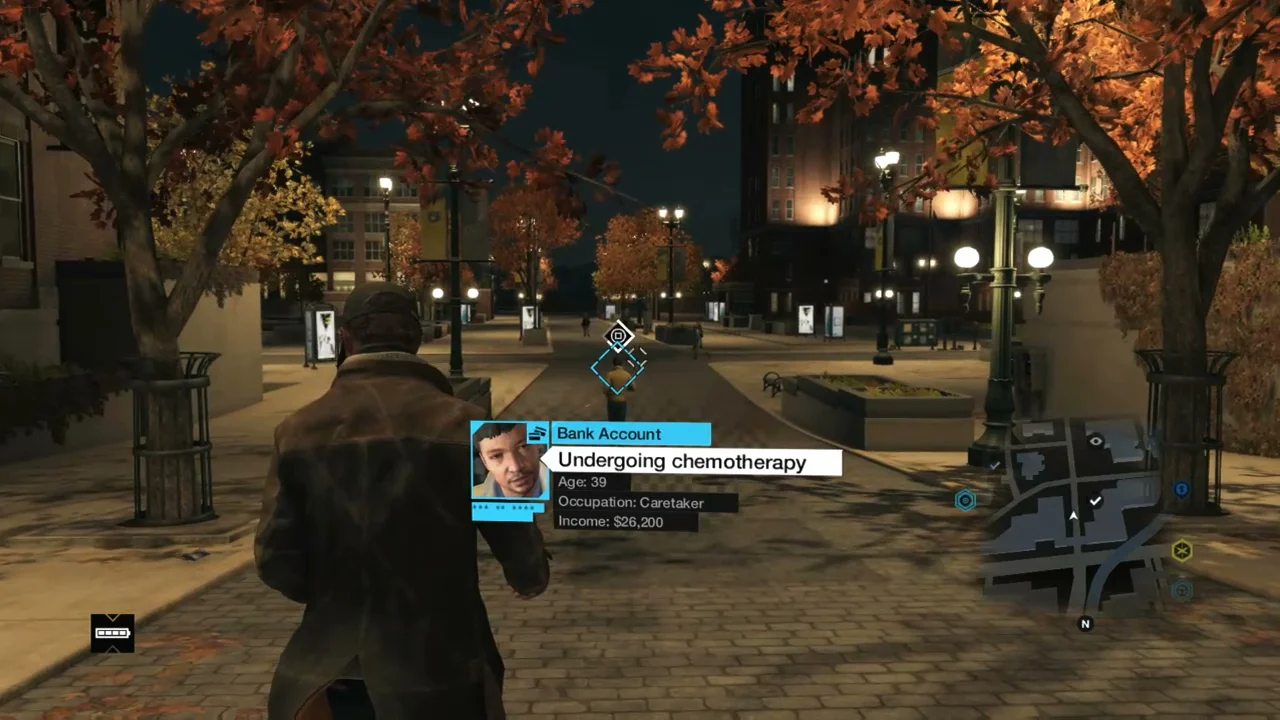

Shortt is the lead story designer of Watch Dogs, and he knows better than anyone the power of Ubisoft's smartphone stealth 'em up when it comes to planting the seeds of narrative. In Watch Dogs, every NPC is like the woman and her baby. Although the game's representation of Chicago doesn't offer a hackable house for every resident, it does give every single one of them a name and a story. When you're walking the streets as Aiden Pearce with your smartphone in hand, you get a window into countless lives, as tooltip windows display snippets of private information linked to their own devices. Maybe you'll get their job. Their income. Their dirty little secrets, like what fetish websites they like to visit. At every turn, at every opportunity, the game puts a face to the faceless.

It all comes from Pearce's ability to tap into a city-wide computer hub that's churning with information. Central Operating System, or CtOS, holds everything on everyone, and as the game progresses it's the gradual chipping away of its defences that bring its powers to your phone. Its first few hours might see those defences reduced by good old fashioned brute force - loud, blunt gunplay, as you eliminate a CtOS substation of its guards - but once you've taken out the enemies and have your way with the digital goodies within, you'll be able to help yourself to an increasing amount of data and security exploits. Smartphone sniffers lead to security camera hacks lead to traffic light trojans. If it's got an electronic pulse, it's yours.

The manipulation of the digital leads to manipulation of the organic, and when Watch Dogs applies its wide-sweeping techno powers to an intimate, human scale, with its endless fountain of citizen information, it elicits a strange sensation. Such power over an unsuspecting target feels like technological voyeurism, where the power to watch is equal to the power to destroy. These people, they have no idea you're snooping through their information. They don't know you know what you know. They're on the other side of a one way mirror; you're the one in control. It's a constant test of morality, a constant dare. What sort of person will you allow yourself to be?

It's a unique feeling in comparison to other free roaming sandboxes. Traditionally, such spaces are sold on a particular culture - a promise, be it implicit or explicit, that gives us not only ability to do what we like, but the permission to do it. Sandbox games say to us "this world is your playground", and as we steal cars, fly planes, and unleash havoc upon pedestrians, we take them up on that offer. Sandbox games are built to foster a certain style of creative exploration, and we use their canvas for our own works, our own whims.

In these worlds, every NPC is part of that landscape, designed to react to our actions. They're set dressing with faces, less human than human. But in Watch Dogs, every NPC has a story. Every NPC is a someone. They have a job, an income. They have secrets. And that's what brings such a simple act as walking down a crowded arcade to a personal level. Would you, could you, with your all-powerful hack attacks, commit a crime against someone after learning their name?

Then again, perhaps this extra level of detail is precisely where open worlds are heading. In Grand Theft Auto V, the series' trademark trick turners now come with snippets of substance. Where once they loitered the corner for the purposes of cheap thrills and schoolyard-level titterings, they now, after the deed is done, are prone to pulling out their phone and calling an unknown party, telling them they've got the money, that maybe we can work this out, that maybe things can be settled. That money, gained from the player, becomes evidence of the level that one person has resorted to in order to pay off a debt. It's not exactly banging with a beardstroke, but it does add a level of personality - perhaps even accountability - to something that had long been little more than a sexy sideshow.

“The power of information is a massive weapon to wield. Watch Dogs continuously aims at a small yet meaningful target and asks you to pull the trigger.”

All too often does a game claim to be a 'living, breathing world'. How many times have we heard that? And the disconnect, such that it has always been, is weird. We're but the main star, the centre of a mini digital universe, where things exist purely for us. We are the catalyst. But if a game can make us feel as though things have always existed, that a city's residents have lives and stories outside of our involvement... what then?

The power of information is a massive weapon to wield. Watch Dogs continuously aims at a small yet meaningful target and asks you to pull the trigger. And I want to play it again. I want to return to that webcam inside that apartment, to hear that baby crying, the mother's soft singing. I want to look at that phone on the kitchen table and I want to leave it alone, knowing that I did the right thing.